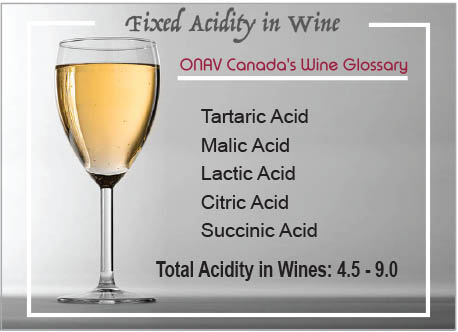

Fixed Acidity in wine

Fixed acidity in wines is determined by the total amount of non-volatile organic acids. The most important fixed acids in wine are tartaric acid, malic acid, lactic acid, citric acid, and succinic acid. Lactic acid is created primarily during malolactic fermentation, when malic and citric acids degrade and transform into the softer lactic acid.

The substances responsible for fixed acidity in grapes are present in the berry itself and are one of the key parameters for determining harvest time. In white wines, especially sparkling wines, acidity is the key component of the flavor profile. In sweet wines, it serves to balance the residual sugars, making the wine fresh and balanced. In Italy, the law permits the correction of wine acidity, in order to improve its taste, stability, and longevity.

Must and wine acidification occurs using the same organic acids already present in the original grapes. The winemaker can intervene both on the fermenting must and after fermentation is complete. In the former case, since the goal is to both raise the total acidity and lower the pH, stronger acids are added. Otherwise, weak acids are used in the finished wine, those capable of altering the acidity but not significantly affecting the pH. The acids permitted by law are:

Tartaric acid, max. 2.5 g/l

Malic acid, max. 1.35 g/l for musts and 2.25 g/l for wines

Lactic acid, max. 2.25 g/l for musts and 3.75 g/l for wines

If our aim is to deacidify musts or wines, then weak bases, both organic and inorganic, can be added, such as potassium bicarbonate, which is permitted by law up to a maximum of 1 g/l, which acts on tartaric acid, lowering its strength and causing it to precipitate in the form of potassium tartrates.

The total acidity of wines is the sum of the fixed and volatile acids present in the must and the wine. It can vary from 4 to 15 g/L and is expressed in grams of tartaric acid equivalent.